Written by: Prof. Lisa Pine

Livia Bitton-Jackson was born as Elli Friedmann on 28 February 1931. She grew up in Samorin (Somorja), Czechoslovakia, a small farming town at the edge of the Carpathian foothills, which became part of Hungary in 1938. Bitton-Jackson turned thirteen in February 1944 and arrived at Auschwitz three months later. She set down her experiences at Auschwitz, published as I Have Lived a Thousand Years: Growing Up in the Holocaust, in 1999, in order to assist new and future generations to learn from the past: ‘My hope is that learning about past evils will help us to avoid them in the future. My hope is that learning what horrors can result from prejudice and intolerance, we can cultivate a commitment to fight prejudice and intolerance. It is for this reason that I wrote my recollections of the horror.’ The Holocaust is a ‘lesson for the future’, she states. ‘My stories are of gas chambers, shootings, electrified fences, torture, scorching sun, mental abuse, and constant threat of death. But they are also stories of faith, hope, triumph and love… My story is my message. Never give up.’

Livia Bitton-Jackson was born as Elli Friedmann on 28 February 1931. She grew up in Samorin (Somorja), Czechoslovakia, a small farming town at the edge of the Carpathian foothills, which became part of Hungary in 1938. Bitton-Jackson turned thirteen in February 1944 and arrived at Auschwitz three months later. She set down her experiences at Auschwitz, published as I Have Lived a Thousand Years: Growing Up in the Holocaust, in 1999, in order to assist new and future generations to learn from the past: ‘My hope is that learning about past evils will help us to avoid them in the future. My hope is that learning what horrors can result from prejudice and intolerance, we can cultivate a commitment to fight prejudice and intolerance. It is for this reason that I wrote my recollections of the horror.’ The Holocaust is a ‘lesson for the future’, she states. ‘My stories are of gas chambers, shootings, electrified fences, torture, scorching sun, mental abuse, and constant threat of death. But they are also stories of faith, hope, triumph and love… My story is my message. Never give up.’

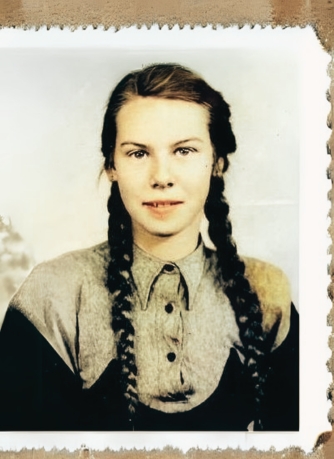

Bitton-Jackson came from a middle-class family and her aspiration was to become a poet. The impact of the Nazi occupation of Hungary and the worsening political situation deeply affected her family, with her father’s business confiscated. Her school years were filled with struggles, apprehension, excitement, sharing secrets and ‘moments of hilarity’ with classmates. She received the coveted class ‘honour scroll’ at school and was flattered and excited to receive the attention of the school ‘heart-throb’, Jancsi Novak. However, her happiness was ruined when Jancsi noticed the yellow star on her jacket. She describes Somorja in lyrical terms, creating the image of a pastoral idyll: ‘The lovely hills loom in a blue haze towards the west… the Danube, the cool rapid river, pulsates with the promise of life…. We children splash all summer in the Danube. Families picnic in the grass, the local soccer team has its practice field nearby, and the swimming team trains for its annual meet’. Yet all too soon, these images of security and happiness were replaced with a sense of foreboding, as the secure environment turned to one of persecution and fear.

The Hungarian military police raided Jewish homes in the middle of the night, during which they harassed and intimidated Jewish citizens, and took whatever they wanted. Her school closed down suddenly and she experienced anti-Semitic harassment and persecution by a group of boys, chanting ‘Down with the Jews’ and ‘Hey, Jew Girl’. Having had to register at the town hall, and give up their valuables, the Jews were removed from Somorja to the over-crowded ghetto at Nagymagyar, where food was scarce. Subsequently, the ghetto was liquidated. The Jews had to give up their remaining possessions and were taken from the ghetto in horse-drawn wagons, handed over from Hungarian soldiers to the SS. They arrived at Dunaszerdahely, marched from the synagogue to the train station, packed into wagons and four nights later, they arrived at Auschwitz.

After her liberation, Bitton-Jackson writes: ‘Dare I enjoy the luxury of being a girl?’ Moreover, she describes how at the age of fourteen, she was mistaken for being an elderly woman: ‘I am fourteen, and I have lived a thousand years’. These two statements encapsulate the scope of the impact of internment at Auschwitz on a teenage girl who survived - lost youth, lost innocence and the gaining of a great burden.

Livia, her mother and her brother, Bubi, were liberated in 1945. Bubi went to the United States to study, and she and her mother subsequently went to the United States on a refugee boat in 1951. She received a PhD in Hebrew culture and Jewish history from New York University. She was a professor of history at City University of New York for thirty-seven years. Bitton-Jackson spent the later years of her life living in Israel. She died on 17 May 2023, aged 92.