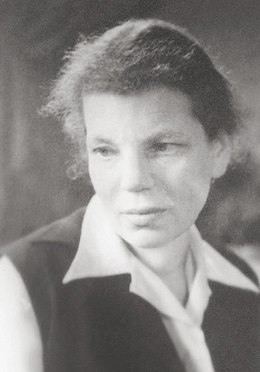

Gertrud Luckner (1900-1995)

Gedenkstätte Deutscher Widerstand archives

Written by: Dr. Carol Rittner, RSM

It seems almost a cliché to call Gertrude Luckner extraordinary, but that is what she was

– extraordinary. When most ordinary people in Nazi-dominated Germany were turning

their backs on their Jewish neighbors and colleagues, Gertrud Luckner was looking for

ways to help them. When most ordinary Germans closed their eyes not to notice that Jews

were being forced out of Nazi Germany, Gertrud Luckner was looking for ways to

connect them with her contacts in England and elsewhere so they might find a place of

refuge. When so many ordinary citizens in Nazi Germany refused to extend a helping

hand to infirm and elderly Jews who had no one to look after them, Gertrud Luckner

conspired with her friend Rabbi Leo Baeck in Berlin to visit them and to bring them food

and medicine to them so they would not feel alone and abandoned. And when the Nazis

began to arrest and deport the Jews of Germany to concentration camps in Poland,

Gertrud Luckner, a slightly built, intelligent, and fearless woman, risked her life to help

hide and save Jewish men, women and children.

Who was this woman who refused to be daunted by the Nazis and the Holocaust?

Who was this Catholic woman who refused to be infected with the theological anti-

Judaism coursing through her religious tradition and the racist antisemtism animating her

society? And who was this German woman of courage who after 1945 refused to give in

to the physical and psychological aftereffects she endured following years of Nazi

harassment, torment, and imprisonment during World War II and the Holocaust?

Gertrud Luckner was born to German parents in Liverpool, England on

September 26, 1900. They returned to Germany when Gertrud was six years old. Her

parents, still quite young, died after World War I. She had no brothers or sisters and once

said, “my family was a small part of my life.” 1 The war, however, was not a small part of

her life. It impacted her greatly, and while she missed out on some regular schooling

because of the war, she developed an early and abiding interest in social welfare and in

international solidarity. “I was always against war,” she said, and “so I got involved with

a very international group. I received my degree from Frankfurt am Main in 1920, in the

political science department.” 2 She went on to study economics, with a specialization in

social welfare, in Birmingham, England (at the Quaker college for religious and social

work). She returned to Germany in 1931, shocked by the popular support Hitler and the

Nazis had, “appalled at the Nazi vocabulary of women students in Freiburg.” 3 She

obtained her doctorate from the University of Freiburg in 1938, just as Hitler and the

Nazis were consolidating their power, stepping up their harassment and persecution of

Jews in Germany, and preparing for all-out war in Europe.

A trained social worker, Luckner worked with the German Catholic Caritas

organization in Freiburg. She was active in the German Resistance to Nazism and was

also a member of the banned German Catholic Peace Movement (Friedensbund

deutscher Katholiken). When it became increasingly difficult for Jews in Germany, she

travelled throughout the country, giving assistance to Jewish families wherever and

whenever she could.

2

Even before the Nazis came to power in Germany (1933) and before World War

II and the Holocaust, Gertrud Luckner already was ecumenical in mind and spirit. She

had been raised as a Quaker, but she became a Catholic after hearing and being impressed

by the Italian Catholic priest and politician Father Luigi Sturzo (1871-1959) “in a packed

hall at the University of Birmingham in 1927.” 4 For her, religion was about compassion,

reaching out, from one person to another, a favorite method of hers “with which she

worked magic.” 5 What mattered to her were human beings and their well being. Her

political views, influenced by her Quaker upbringing and her Catholic social justice

views, contributed to her early identification of Hitler’s political and international

danger. 6

After the outbreak of World War II in 1939, she organized within the Caritas

organization, with the blessing and active support of Freiburg’s Catholic Archbishop

Conrad Gröber, a special “Office for Religious War Relief ” (Kirchliche

Kriegshilfsstelle). Although the record of the institutional Christian Churches – Catholic

and Protestant alike – in Germany during the Nazi era and the Holocaust is less than

exemplary, there were individual church people – clergy and laity alike – who did try to

help people who were being persecuted by the Nazis. And while Archbishop Gröber was

not what one would call an outstanding anti-Nazi resistor, neither was he a rabid

supporter of Hitler and the Nazis. As the war wore on, the Office for War Relief became

in effect the instrument of the Freiburg Catholics for helping racially persecuted “non-

Aryans,” which included both Jews and Christians. While Gertrud Luckner was the

driving force behind this relief effort, She used monies she received from the archbishop

to help Jews, to smuggle them over the Swiss border to safety, and to pass messages from

the beleaguered German Jewish community to the outside world.

Luckner often worked with Rabbi Leo Baeck, the leader of the Reich Union of

Jews in Germany (Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland), to help the Jews. She

remained in close contact with him until his arrest and deportation to Theresienstadt in

early 1943. Then, on November 5, 1943, as she was on her way by train to Berlin to

transfer 5000 Marks to the last remaining Jews in that city, Luckner was arrested by the

Gestapo. For nine weeks, she was mercilessly interrogated by the Gestapo, but she never

revealed anything. She was sent to Ravensbrück concentration camp where she endured

nineteen harrowing months until she and thousands of other women were liberated by the

Soviet army on May 3, 1945.

Asked why “she did what she did, thereby risking her life” to help Jews and

others who were in danger during the Nazi era, World War II, and the Holocaust, she

always replied, “almost astonished,” that it “was obvious.” What did she mean, it was

“obvious”? Asked if it was “religious conviction” that prompted her to do what she did,

she admitted, with one word, “Probably.” 7

After the war, Gertrud Luckner established a center for Catholic-Jewish

reconciliation in Freiburg, although the mood in the country in the 1950s did not support

such work, nor did the Vatican, but

Having risked her life for Jews and spent the last two years of the war in

Ravenbrück concentration camp, Luckner found it impossible to abandon the

remnant of Jewish humanity that survived the Holocaust. Already forty-five years

old at the war’s end and in poor physical condition, the irrepressible Luckner

decided to dedicate herself anew to fighting German antisemitism and promoting

3

Christian-Jewish reconciliation. Luckner knew it would be a long-term process,

simply because it meant confronting German and Christian anti-Semitism. 8

Luckner established the Freiburg circle, a German dialogue group devoted to

conciliatory work with Jews, as well as a journal, the Freiburger Roundbrief which

because of Luckner’s personal credibility attracted Jewish readers and correspondents of

international reputation. Her friend, Rabbi Leo Baeck survived the war and the

Holocaust. He never forgot that Gertrud Luckner was risking her life to give Jewish

people relief when she was arrested by the Gestapo. After the war, he supported her, and

at his invitation, she visited Israel in 1951, one of the first Germans to do so. It was the

first of several visits to Israel, where there is now a home for the aged named in her honor

Dr. Gertrud Luckner devoted herself to the work of Christian-Jewish

reconciliation. In no small part, it was her persevering work as a Catholic Christian that

helped nudge the Church to begin to come to terms with its long and shameful history of

theological anti-Judaism. While there were others – clergy and lay, women and men –

who also helped the Catholic Church to re-think its religious and practical relationship

with living Jews and Judaism, few were more dedicated to this task than was Gertrud

Luckner. She made an enormous and positive difference to many, many people. On

February 15, 1966, Yad Vashem recognized Gertrud Luckner as Righteous Among the

Nations.

Block, Gay and Malka Drucker. Rescuers: Portraits of Moral Courage in the Holocaust.

New York: Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc., 1992: 146-148.

Petuchowski, Elizabeth. “Gertrud Luckner: Resistance and Assistance. A German

Woman Who Defied Nazis and Aided Jews” in Ministers of Compassion During the Nazi

Period. South Orange, NJ: The Institute of Jewish-Christian Studies, 1999: 5-21.

Phayer, Michael. The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930-1965. Bloomington:

Indiana University Press, 2000.

Phayer, Michael and Eva Fleischner, Cries in the Night: Women Who Challenged the

Holocaust. Kansas City: Sheed & Ward, 1997.

Notes

1 “Gertrud Luckner” in Gay Block and Malka Drucker, Rescuers: Portraits of Moral

Courage in the Holocaust (New York: Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc., 1992) 146.

2 Ibid.

3 Elizabeth Petuchowski, “Gertrud Luckner: Resistance and Assistance. A German

Woman Who Defied Nazis and Aided Jews” in Ministers of Compassion During the Nazi

Period. South Orange, NJ: The Institute of Jewish-Christian Studies, 1999: 7.

4 Ibid, 8.

5 Ibid, 9.

6 Ibid. 8.

7 Ibid, 9.

8 Michael Phayer, The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930-1965 (Bloomington, IN:

Milena Jesenska & Margarete Buber-Neumann